SpaceJam.com and the Lindy Effect: How a Goofy 90s Website Became a Monument

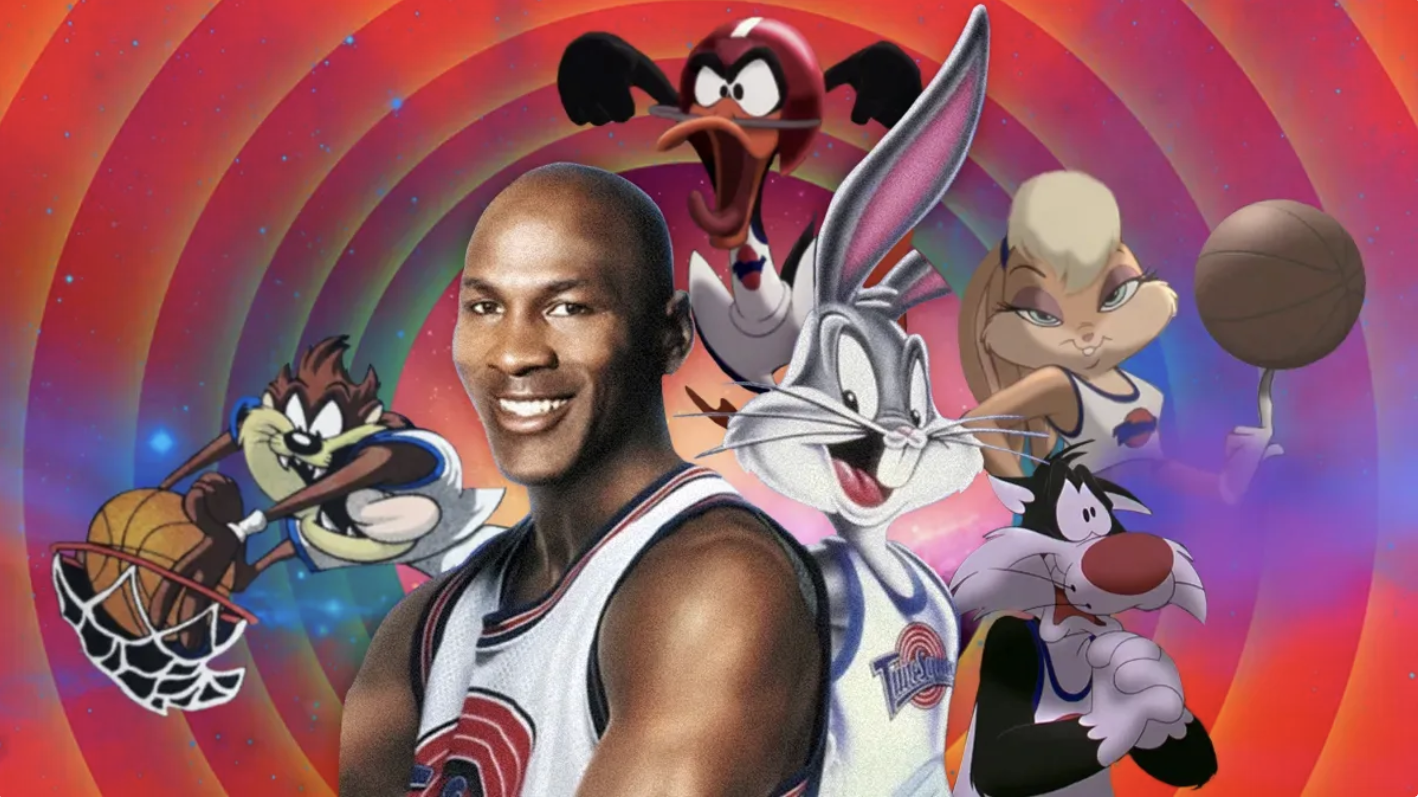

A website for a movie where Michael Jordan teams up with Bugs Bunny should not be one of the most enduring artifacts of internet history, yet here we are. SpaceJam.com, launched in 1996 as a goofy marketing experiment, outlived MySpace, Vine, Flash, and nearly every other relic of the early web.

What was supposed to be a disposable tie-in for an $80 million cartoon–sports comedy became a digital fossil that people could not stop talking about. And the longer it stayed online, untouched and un-updated, the funnier and stranger its survival became. By the time most of the internet rediscovered it in the 2010s, SpaceJam.com was no longer just a website, it was an in-joke, a meme, and eventually, a cultural monument.

Born goofy, stayed goofy

The Space Jam movie itself was weird enough: Michael Jordan fresh off retirement, Looney Tunes characters plucked from Saturday morning, and an alien basketball plot that read like a fever dream of a marketing executive who had not slept in a week. The website matched the chaos.

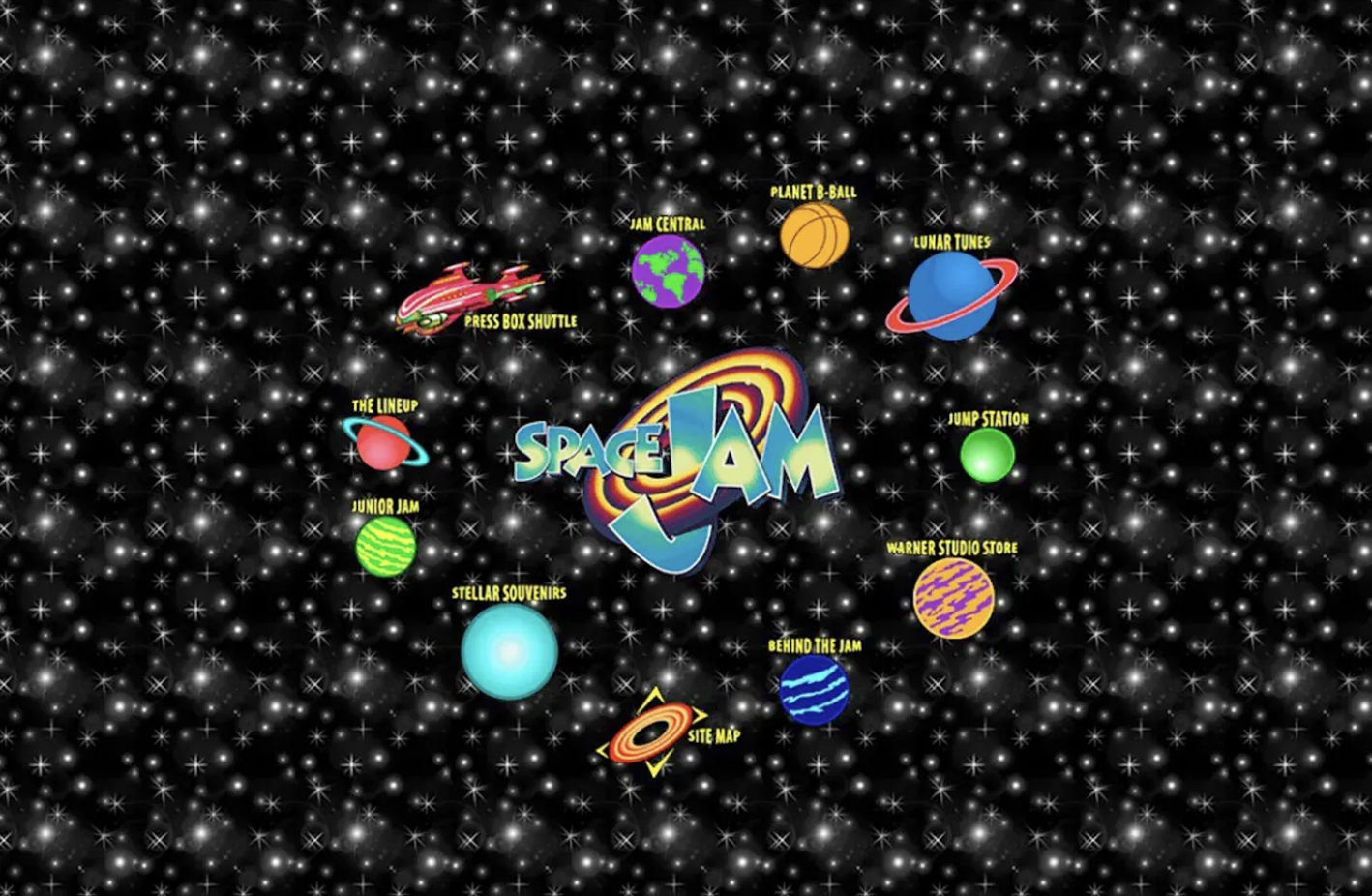

It had all the fashionable trappings of a 1996 site: tiled star backgrounds, image maps you could click through like a treasure hunt, graphics scaled for 640x480 monitors, and breathless copy about “the Information Superhighway.” By modern standards, it looks like the inside of a Trapper Keeper after a can of Surge exploded. By 90s standards, it looked cutting edge.

Movie websites were barely a concept. They were experiments, half-serious attempts to translate posters and trailers into HTML. Most of them disappeared without a trace. SpaceJam.com did not.

Forgotten, then rediscovered

When the movie’s theatrical run ended, the site should have been pulled. That was the pattern for promo domains: they expired, redirected, or collapsed into spam pages selling discount sunglasses. But Warner Bros. never unplugged it. So it just sat there.

For more than a decade, the site stayed online, humming along in obscurity. The world moved on. Flash rose and fell. Social networks exploded, then imploded. Broadband made dial-up seem prehistoric. And in some corner of Warner’s server farm, Bugs Bunny kept welcoming visitors to the Space Jam site.

Then the 2010s arrived, and the internet rediscovered it. Suddenly this strange fossil from the Clinton years was back in circulation. Reddit threads gawked at its pixelated glory. Design blogs praised it as “a cave painting of the web.” Rolling Stone called it “the website that would not die.” What had once seemed disposable now felt profound.

The quiet caretakers

The wild part is that it did not survive by accident. The site was not literally static HTML frozen in amber. Behind the curtain, someone at Warner Bros. was quietly keeping it alive. Hosting costs were covered. Code was patched to dodge browser breakage. Obsolete features were adjusted so they would still function. As they say, not all heroes wear capes.

This was not just a ghost ship drifting through the internet. It was being steered, if only barely, by invisible caretakers. That quiet maintenance gave it a weird romance. It suggested that with a little attention, digital artifacts could actually last. That the internet did not have to eat itself every few years. That a goofy movie promo could become, accidentally, a monument.

The sequel ruins the joke

In 2021, the run ended. Warner Bros. released Space Jam: A New Legacy and suddenly the domain was needed again. Out went the star-tiled fossil. In came a new site filled with glossy animations, autoplaying video, and the same bland design that feels old the moment it is published.

Fans panicked. A piece of internet folklore seemed to vanish overnight. But in a surprisingly generous move, the studio preserved the original. Hidden behind a link and a new address (spacejam.com/1996) the old site still lived. Not gone, just relocated.

Of course, it was no longer perfect. Deep links broke. Some pages stopped functioning. The fossil was now a museum piece. But it was still there, which is more than you can say for most of the internet.

What it says about us

Visiting it now is a bittersweet experience. The site is part artifact, part diorama. But its survival matters. Because it shows how persistence alone can transform something dumb into something profound.

This is the Lindy Effect in action: the idea that the longer something survives, the longer it is likely to keep surviving. Shakespeare’s plays have lasted centuries, so we assume they will last centuries more. Back to the Future has lived in pop culture for forty years, so odds are it will still be quoted in another forty. And improbably, SpaceJam.com has been online for nearly three decades, which means it may outlast much of what we call the internet today.

Nobody thought this site would be remembered. Nobody thought it deserved to be remembered. And yet it became a cultural touchstone, celebrated in classrooms, cited in oral histories, gawked at by people who were barely alive when the movie premiered.

It also says something about us: how we cling to relics when everything else feels disposable, how a goofy little site became a rare constant in a medium defined by erasure, and how survival itself can be a form of cultural rebellion.

Takeaway

The movie was a quirky 90s footnote, but the website became immortal. And, in the restless churn of the internet, maybe that is the bigger achievement: not chasing relevance, not reinventing yourself, but surviving long enough that the world has no choice but to take you seriously.