The Surprising Origin of Email Advertising and the Two Lawyers Behind It

How Two Lawyers Accidentally Opened the Floodgates for Online Advertising

In the spring of 1994, two immigration lawyers from Arizona pressed “send” on a message that quietly detonated beneath the foundation of the early Internet. The post was titled “Green Card Lottery 1994 May Be The Last One!”.

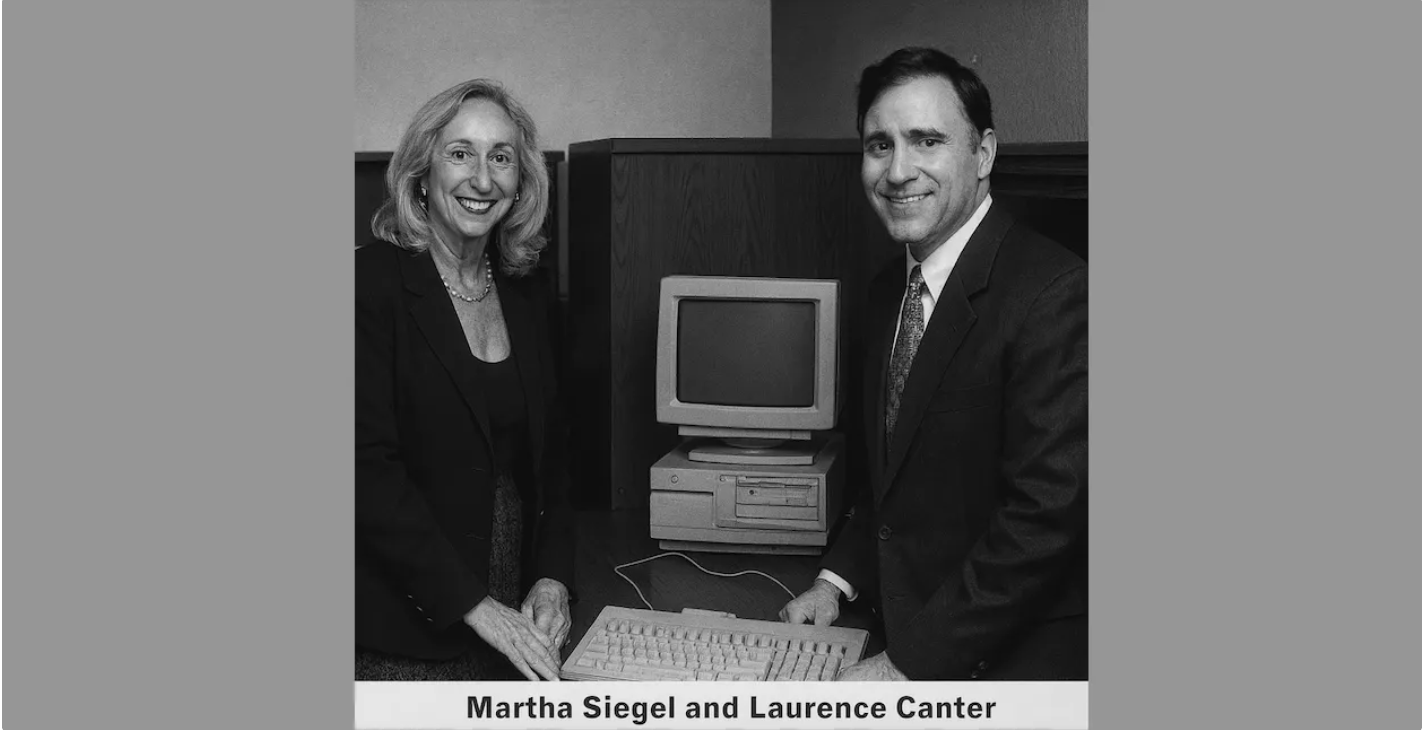

It was a simple advertisement for their legal services helping non-citizens apply for U.S. residency. It was not the first online ad, but the way it was distributed would make history. Laurence Canter and Martha Siegel did not share their pitch in a few small corners of the web. They unleashed it across nearly every Usenet newsgroup in existence, thousands of them, reaching millions of people overnight.

It became the first large-scale commercial spam in Internet history, a single message multiplied thousands of times that forced the online world to confront something it had been avoiding: that connection and commerce were now inseparable.

The Mechanics Behind the Spam

In the mid-1990s, there was no commercial Internet as we know it today. There were no search engines, banner ads, or marketing lists. What existed instead was Usenet, a vast collection of text-based discussion boards hosted on university servers and early Internet providers. Each “newsgroup” focused on a topic such as programming, politics, astronomy, or hobbies, and posts were mirrored across servers around the world. It was both a tool and a community, a place where the early Internet learned to talk to itself.

Users who wanted to share a message typically posted to one or two relevant groups, or cross-posted a single message to several related ones so that readers wouldn’t see duplicates. Canter and Siegel ignored all of that. Their goal was saturation. They wanted every potential client for their immigration practice to see their message, regardless of topic or geography.

Since they lacked the technical skill to do it themselves, they hired a local programmer known only as “Jason.” He wrote a short script in Perl, a language designed for text processing and network automation. The script pulled the complete list of active Usenet groups and automatically posted a copy of the same ad to each one. Because each message was unique to its group, it bypassed duplication limits.

On April 12, 1994, the lawyers ran the script. Within hours, their ad spread to nearly every corner of Usenet (roughly 5,500 to 6,000 groups). The same headline appeared again and again until it filled the digital horizon. For anyone who participated in multiple communities, it felt like the Internet itself had been taken over by a single message.

The reaction was immediate. Servers slowed, administrators were bombarded with complaints, and Internet Direct, the couple’s provider in Phoenix, received so much hate mail that its systems crashed entirely. Within forty-eight hours, the company terminated their account.

By the time Internet Direct cut the lawyers off, the damage had already spread too far to contain. The Green Card ad was everywhere, copied and discussed, cited as the first act of mass intrusion into an online community. What made it extraordinary wasn’t just the scale of the message but how it exposed a structural truth: the Internet had no immune system.

The post had gone viral long before that term existed. It proved that a small piece of automation, combined with global distribution, could overwhelm human conversation entirely.

Although people were annoyed with the unsolicited messages, the lawyers saw success. They claimed the campaign brought them thousands of responses and tens of thousands of dollars in business. To them, the outrage proved that they had discovered a new kind of reach. What began as a crude advertising experiment became the first large-scale example of automation hijacking human attention.

Outrage Becomes Opportunity

While the Internet recoiled, Canter and Siegel celebrated. They saw themselves not as offenders but as entrepreneurs. Their law practice gained attention, and the attention convinced them they had found a new business model. Within months, they founded a company called Cybersell, offering “Internet marketing services” to other businesses. They published a book titled How to Make a Fortune on the Information Superhighway and began presenting themselves as experts in digital promotion.

To engineers, they were reckless opportunists. To themselves, they were visionaries who had glimpsed the future of commerce. In truth, both were right. Their act revealed something essential about the Internet’s design: openness could be used as leverage. Once someone realized that attention could be scaled, the era of online marketing had already begun.

The Internet Strikes Back

The community’s response went beyond anger. Within days, developers created tools called cancelbots; scripts that could automatically find and delete copies of the Green Card ad across Usenet. It was the first large-scale experiment in algorithmic moderation. For the first time, the Internet was learning how to defend itself against itself.

The Green Card Spam also sparked a philosophical reckoning. The Internet’s early culture had been built on freedom, but now that freedom had a cost. Users began to ask who should decide what belonged online and how much control any one group should have. Those questions became the blueprint for future debates about moderation, speech, and governance that still define digital life today.

The Commercial Turn

The timing of the Green Card Spam could not have been more symbolic. Just months later, domain registration for commercial sites opened to the public. The web, once academic and idealistic, became a marketplace. Network Solutions began charging for domains, and companies like Pizza Hut, Wired, and Yahoo launched their first websites.

Canter and Siegel had not created that transformation, but they embodied it. Their crude campaign previewed the new logic of the web: reach everyone first, deal with consequences later. Attention replaced authority as the new currency of influence. What had once been a network of collaboration was quickly evolving into an economy of visibility.

Their ad became the prototype for the attention economy that followed. The traits that made it offensive, (automation, repetition, disregard for boundaries), became the same traits that defined the next generation of online success.

Fallout and Legacy

Canter and Siegel’s personal story unraveled as quickly as it had exploded. By 1997, Laurence Canter was disbarred for unethical conduct, and Cybersell quietly shut down. Yet the mechanism they had unleashed never went away. Every email blast, viral post, or algorithmic campaign still relies on the same principle: automate, amplify, and monetize.

The Green Card Spam forced the Internet to confront its defining paradox. The very openness that made it powerful also made it vulnerable. The same infrastructure that connected people could just as easily be used to exploit them. That tension between connection and control has shaped every era of online life since.

Our Take On It

The Internet did not lose its innocence in a boardroom or during a billion-dollar IPO. It lost it in a Usenet post. Two lawyers hit “send,” and the web discovered its most powerful and most dangerous capability: reach.

Canter and Siegel were not geniuses or villains, they were simply early. They tested what the Internet could tolerate and proved that information, once multiplied and monetized, could become the most valuable product of all.

The Green Card Spam didn’t just break etiquette; it exposed the Internet’s identity. It showed that the same tools built for communication could be used for persuasion, and that every connection carried the potential for conversion. What began as a single, repetitive message became the accidental prototype for the world’s largest economy, built not on goods but on attention.

Once those six thousand messages flooded the network, the future of the Internet was already written.